An Invitation to a Class Reunion: A Letter from the Past

Published 2:13 pm Thursday, April 24, 2025

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

My father, Dick Gollwitzer, passed away recently at the age of 95. As I sorted through the keepsakes he had carried with him through a lifetime, I came across something that made me pause—a typed letter from 1985, inviting his high school classmates to a reunion.

He often told me how much he loved Berea High School in Ohio. After graduation, he missed it so deeply that he wished he could return and never leave. For many years, he helped organize reunions for the Berea High School Class of 1945. His role was to write the invitation letters — passionate, visual, warm and inviting messages that somehow captured the soul of his class and the town they shared.

This letter, written four decades after his graduation, is one of those. It reads like a short story, full of memory and meaning. And though it was addressed to his classmates in the small town where he grew up, I share it now because the feelings he evokes—of belonging, nostalgia, and enduring friendship—could belong to any town in America, or anywhere else. The names and streets may change, but the sentiment is universal.

I’ve never attended a high school reunion. I’m not even sure why. Maybe I thought they were awkward, or maybe I was just shy. But had I received an invitation like this, I think I would have gone.

Here is the full letter, in my father’s own words:

Jan. 10, 1985

“It was the best of times; it was the worst of times.”

The worst of times, surely: The worst depression in the history of the republic. College graduates in the WPA. Soup lines. Kids taking lard sandwiches to school and putting cardboard in their shoes. The banks failed. Mortgages were foreclosed.

Teachers worked without pay. Socks were darned. Baths were taken once a week. Clothes were patched and handed along. Even the rich were poor.

All this dragged on for 12 long years. The Depression, it seemed, could only be cured by something catastrophic. We got it — the War. The most vicious, all-encompassing war in the history of the world. Boys we knew went off and never came back — some came back but had parts missing. Food was rationed. Gas was rationed. Life was rationed. Death took our friends. Bob Krenkel left school for the Army, and six weeks later was killed in France.

And yet, in Berea, Ohio, it was the best of times: Nobody locked their doors. Everybody knew everybody, and everything about everybody. No pretense there. On crisp fall nights, the whistle of the majorette and the thump of drums drew us to other battles. Lakewood vs. Berea.

Average-size boys in oversized uniforms fought for their team, their school, their manhood. Trim girls in red and blue jumped toward the harvest moon and exhorted the crowd to give them a B, give them an E, give them an R-E-A. The cheers and drums could be heard by people on the Triangle, by dogs on Baker Street, by the horses at the fairground — and we can hear them yet on certain autumn nights, if we hold our heads just right.

After the game, there was Jackson’s for hamburgers… happy days… Camelot.

There were hayrides and get-acquainted goings-on in the back of Model A’s. There were kisses. There were virgins in those days (some were precocious). There was the Standard Drug Store after school, with its green penny scale where we were actually proud to gain weight.

And Otto Mahler’s place — Gray’s Candy Kitchen. The smell of popcorn blowing out into the Triangle. Otto’s back room. Eskimo Pies. Romance over sodas.

And the movies — the golden days of movies: Going My Way, The Maltese Falcon. Bogart, Gable, Cooper, Lamarr, Grable. The old movie house next to Meilander’s Ice House was full every night. It was the only game in town. Ann Seaton sold tickets. Gene Norris, Bruce Mattison and I were ushers. Wednesday night was Bank Night.

The best of times, surely.

Living through all this, taking the scars of all this, having their personalities formed and deformed by it, was a group who spent their days together for 180 days a year, some for 12 years. They went to class together and learned about life and love and success and failure. They were all afflicted by the times. No one was not marked.

They were a class unto themselves — the Berea High School Class of 1945.

It was different for each of us, but common to all of us. No one can join this class. No one can be dropped out. If you were in it, you are in it — for good and all.

The friends we had then were the standard for all later acquaintances. The thousands of people we’ve met since slide off in our memories. We forget their names. But can we forget a name like Emil Pastorek… Franklin Hitt? Does a cat have an ass?

Then, in June of ’45, we got together for the last time, and someone gave a speech, and we left each other abruptly and went out into the world.

For 40 years we’ve been out there — working, laughing, drinking, crying, loving, breeding, divorcing, dying. Getting high, getting low, getting sick and fat and old and gray and bald and tired… and maybe wise.

Whatever we thought life was when we walked out — it was more. It was less. If we’re lucky, we’re still in it. There’s more to come: the last act.

Maybe you’d like to go back again “to the days of yesteryear” and see them all again. Maybe not. Perhaps we should never look back — just remember everybody as they were in the prime of their budding, young and beautiful.

It might be painful now. It might be a trip we’d be sorry we took.

But then again, it might be really neat and satisfying to spend a couple of days wandering around a hotel where everybody has a name you could never, would never, ever forget. What stories we could tell. What stories we will never tell.

It should be an absolutely great experience — an intermission. And it might even make some new old friends who can be with us through the last act.

Old friends are the best friends, after all.

— Dick Gollwitzer, BHS Class of 1945

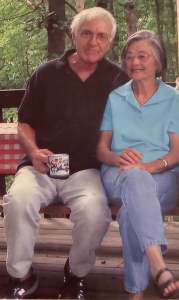

As the days pass since the loss of both my mother and father, I find that I can hardly read his words — out loud or even silently — without choking up. I miss them both dearly.