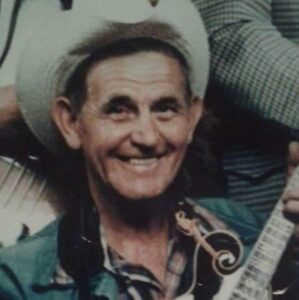

A man and his music

Published 10:04 am Monday, December 2, 2024

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

By Josh Lanier

The first time I met my wife’s grandfather, Paul Hardin, he asked me if I knew how to play, and I just nodded and said a little bit.

He cradled his mandolin in the crook of his arm and pointed over beside the couch at a dusty old guitar case standing in the corner. Inside was a shiny Gibson Hummingbird, the first I’d ever seen in person, much less held in my hands. Paul told me to start off in G in 4/4 time, and he’d let me know when to change. He counted us off, and I did the best I could to hang on.

Trending

The sound coming from the f-holes of his old mandolin rang out over my clumsy accompaniment, drifted out the open windows and screen door of that mill house in Greenville and filled the air with a melody as ancient to me as the hills from which it came.

Paul Manning Hardin, November 2, 1916 – January 28, 2008

Melissa and I visited her grandparents on our very first date when we were both sixteen. We weren’t officially “dating” yet, but she said if they asked, we were already boyfriend and girlfriend because she didn’t want to have to explain we had just started talking on the phone. Paul gripped my hand like a man thirty years younger, and he asked me if I cared to arm wrestle him, as he did everyone, male or female, that entered his house. Although several strokes had caused his legs to fail him, he still prided himself in having strong arms and hands.

When the subject of music came up, he was eager to show me that he still had the touch, and it was also a test for me. Our shared love for bluegrass music helped me garner his approval, and he gave his blessing to “court” his granddaughter. I knew that day that she was the one.

Despite his limited mobility and macular degeneration slowly taking his eyesight, Paul still had a keen ear for music, and even in his late eighties, his hands flew across the strings effortlessly. On almost every Sunday evening after, as he and I sat on his front porch with our instruments across our laps, he would tell me stories from his early days.

He had ran away from the farm up near the Dark Corner as a young boy, hopped trains and lived the life of a hobo. His chance to see the world was from the boxcar of a train. Paul told me that he had rode the Orange Blossom Special from New York City to Miami, Florida. All the while, he was learning to play music. He fell head over heels for Bluegrass the first time he heard Bill Monroe’s “Mule Skinner Blues” on the radio in the 1940s.

Paul and his band played mountain music all over the place for years, continuing even after he’d married and had to take a job at the mill to support what ended up being eight children. He never made it big like other Bluegrass pickers of his caliber, but it didn’t matter to Paul. To him, it was always about the music.

Trending

Today, as I listen to some of my favorite bluegrass musicians of this modern era, I wonder what Paul would have thought about the recent resurgence of the genre. I believe he would get a kick out of listening to the likes of Billy Strings, Dan Tyminski, Molly Tuttle, and the Infamous Stringdusters. And I believe he would be exceptionally proud of all the local talent in our own region who keep the tradition of Bluegrass alive.