How Aaron Greene’s belief in Polk County’s kids built a legacy of excellence

Published 8:26 am Wednesday, July 2, 2025

- Polk County Schools Superintendent Aaron Greene leads staff and students into Tennant Stadium for Polk County High School's 2025 graduation ceremony.

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

The small trophy never lets Aaron Greene forget how and where his journey to leadership began.

It sits quietly in his home office, nothing remarkable about its appearance, yet everything notable about its presence. Greene received it during his senior year at Newton-Conover High School, statewide recognition for citizenship during his tenure as student council president.

Newton-Conover staff nominated Greene because they saw his potential to lead, saw room for continued growth following a year in which Greene both lost a parent and decided the course of his life wasn’t heading on a path worth following.

Seeing others believe in his ability to lead meant just as much to Greene as the trophy he won for doing so. And, for the third time in the space of a few years, an educator delivered that impact.

Neither lesson was lost.

“I remember thinking, well, that’s pretty cool,” Greene said of the state honor. “I get an award about being not just a good citizen, but a good leader?

“That little cup is in my room, and it actually humbles me. It doesn’t make me feel like I’m better than everybody else, but it really reminds me that every single person you see, everybody you know has value, they have worth. And it’s worth your time and energy to invest in them. It was such a good lesson for me to learn at that age.”

And one he’s spent largely every day since paying forward.

Building sincere student relationships has been a hallmark of Aaron Greene’s time in Polk County

The last Monday in June will close Aaron Greene’s time with Polk County Schools – three decades as a teacher, principal and district administrator, culminating in nine years as superintendent, reaching its conclusion.

It’s a decision that Greene made some time ago and with which he is more than comfortable, primarily for the reasons he made it. Greene has embraced Polk County Schools as his second family, caring and nurturing for its students and staff as if they were his own. Now it’s time to give his true family its turn.

“There were a lot of sacrifices my mom made for me growing up, and so now when she’s in the twilight of her life and she needs people to make sacrifices for her, I certainly want to be there for that,” Greene said.

“And there’s even my own health. Over time, the job takes a toll on you physically. I want to live a little bit longer, so I think for a variety of reasons it’s a good decision. But, yes, my mom, (wife Mary)’s family, they’re getting up in years, and so it’s a good time in our lives to try to give back to the people who really invested in us.”

The peace that has come with the decision has not arrived without a bittersweet tinge. Thirty years of building relationships – hiring teachers, watching students grow and return with their own children, working with leaders across the state – means a lot of friends and acquaintances to which to say goodbye. It has been perhaps the most challenging aspect of his decision.

“I will miss the people who do unbelievable things and go way above and beyond for our kids and our families when they don’t have to do so,” Greene said. “It makes you work that much harder because you see that going on.

“I’ll miss the kids. I’ll miss the relationships. I love the cyclical nature of the year. I like being able to start over. Here’s the culmination of our work with graduation, and then, bam, you turn around and you start anew. So that first day of school with that last day of school were pretty cool.”

Greene spent the majority of his time in Polk County as a leader, out of the classroom. But it’s there, where his career began in 1994 as a math teacher, that his passion remains. How Greene has interacted with students, often meeting them in their language and on their terms, has been a hallmark of his educational career. He especially felt at home at Polk County High School, where he served for more than half of his tenure as a teacher, assistant principal and principal.

“I love being in the classroom. I love being a principal around the kids,” Greene said. “That’s where I got my energy from. Teenagers are awesome. I know a lot of people don’t like to work with teenagers, but they are incredible. And I know that that was an important time in my life and I just always felt good about giving back to that age group.”

The flip side of building deep relationships, of fostering a family-like atmosphere, is the resulting sense of needing to take care of all of those people, and Greene certainly felt that strongly. His tenure as Polk County’s superintendent included some of the most challenging times in the district’s history – mudslides, a pandemic, political unrest, state and federal funding challenges, the destructive aftermath of Hurricane Helene. Those situations were often far removed from test scores and bus routes and the everyday things that many often envision as a superintendent’s main concerns.

They’re foremost among the things that Greene will not miss about his role.

“I think the hardest thing for me is the pressure,” Greene said. “And I actually admire people who can compartmentalize better than me, but when you care, that immense pressure you feel to take care of everybody, to make every decision the right way, it’s there. And I think if you talk to administrators or anybody in a position like that, they’ll tell you the same thing. But that’s the challenge for me, you’re really on an island. There’s nobody you can call and talk to about it.

“Unfortunately, we’ve seen education take a different turn in this state and nationally in terms of public ed. So I won’t miss the politics. I won’t miss begging for what I would consider to be the minimum resources we need to function. I certainly won’t miss the drama. I won’t miss people’s personal agendas that often get in the way of progress, and I won’t miss the paperwork and jumping through the hoops, either.”

Life changed dramatically for the mischievous young Aaron Greene when he was seven.

Watching parents divorce will do that to a child, and Greene was no different. But just when he needed a break, a ray of sunshine, an educator stepped in and provided just that.

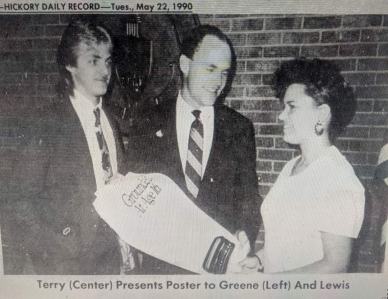

“I distinctly remember Donna Irvin was my teacher after the divorce, right along that time,” Greene said. “And there was a stupid competition they were having about kids in elementary making posters for fire prevention. And every year, the posters looked about the same, it wasn’t anything earth-shattering.

“But I think she always knew and could tell that I needed a little bit of a lift, that here’s this kid going through a rough time, he looks a little depressed. And so she submitted my poster as the winning one, they got to take a picture. And I just remember that time in my life thinking, okay, somebody does believe in me, somebody cares about me. And then later on, reflecting back on that, you realize what kind of power and influence educators who care and do things the right way, what they have.”

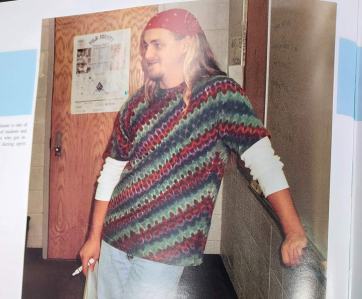

Motorcycle engine blaring, long hair flowing in the breeze, Aaron Greene arrived in Polk County to interview for a job he considered nothing more than a stepping stone.

The recent Appalachian State graduate struggled even to find how to get to Polk County. “I really got a little worried. I couldn’t find how to get onto 108 from 221. It’s convoluted in Rutherfordton,” Greene said.

Once he arrived, roaring up on his bike to first interview with Geoffrey Tennant, Greene’s first thoughts were mainly about getting hired and seeing how quickly he could find another job closer to friends in Henderson or Buncombe counties.

It took maybe a year for that urge to move to fade away.

“Really, after the first year here, you realize what good people there were,” Greene said. “Loved the kids, loved the environment. The school was fairly new, a beautiful facility. So I got hooked.”

A yearbook photo from Greene’s early years captures his young adult persona – passionately addressing a room full of students, a bandana wrapped around the long hair.

That guy might not recognize the later version of himself, the one wearing a suit and tie every day, often spending weeks in Raleigh talking with state legislators about the funding needs of rural school districts or walking across the street from Stearns Education Center to address Polk County Board of Commissioners’ meetings. Yet while the style of dress has changed and the hair gotten a bit shorter, the motivation for that man, young and old, has never wavered.

“I think I’m still surprised that that guy was in there,” Greene said with a laugh. “There was a time when I really thought I would be in a band, in a rock band. I did that when I was younger. I thought I might be a studio engineer. But I think we all evolve over life and we realize that there may be a spot for us we didn’t imagine.

“So I’m not going to tell you I don’t miss that guy from time to time, but it was certainly rewarding and, let’s face it, beneficial over the long term to turn that corner. I would argue that in a lot of ways, that guy’s still in there. But I think there’s a constant string that’s run through all of that inside that I want to make sure that I give back. And it doesn’t matter whether you have long hair and a tie-dye T-shirt or wearing a tie. You can still do those things.”

But what would younger Greene have thought of his more button-downed future?

“He would’ve laughed and he would’ve said, man, you’re an idiot. What are you doing?” Greene mused.

Greene eventually married Polk County native Mary Metcalf, further cementing the roots he’d begun to plant in the area. And as he followed his mentor Bill Miller first into the principal’s seat at Polk County High, then to the district offices at Stearns, Polk County’s academic fortunes also began to reverse.

The small district steadily evolved into one of North Carolina’s best, its student performance rivaling, often exceeding, the state’s largest districts. It became routine for the district to finish among the top five in the state for student achievement on end-of-year exams. Websites such as Niche.com routinely lauded Polk County Schools as the state’s best in many areas. No matter the criteria, Polk County held its own with any district in North Carolina.

The community into which Greene fully immersed himself had much to do with that, he noted.

“I think you’ve got to mention size, the fact that we’re a smaller district and we can have those strong relationships,” Greene said. “But again, the people make the difference. I find it fascinating that when I got here, you’d always heard about retirees don’t like paying taxes, their kids are already out of school. But it was the opposite here – you have a very vibrant retirement community that provides a lot of culture mentoring and certainly a tax base and a revenue stream that helps the schools. The community also, I believe for the most part, trusted us and still does to take care of their kids. That has to happen. You can’t do this work in isolation.

“And then I don’t know that I’ve found a spot that, on a per-capita basis, has quite the level of philanthropy that Polk County does. And whether you’re talking about feeding kids or scholarship money for kids or just hey, is that a need? Mental health is a need, whatever it may be. And not just for school, but stepping up for the entire community. I’ve always been amazed that you have people like Geoff Tennant and Margaret Forbes and people who are continuing their legacy to this day. That makes a big difference. When you’re trying to do good things for kids, it’s allowed us to do a lot of extra.

“So people would ask us, how do you get these results? How do you get these scores? And we would tell them, unless you can take our entire community, our people, the dynamic between them, if you can take that and sit it down where you are, then fine. But if not, I can’t tell you. I don’t know what that looks like.”

Aaron Greene served as Newton-Conover High School’s student council president during his senior year

Alan Greene died when his only son was a junior in high school.

As he managed his grief, though, Aaron Greene realized that “life’s too short to be messing it away.” So he made some changes, began planning and preparing for life after high school, began thinking about what he could do and be.

Once again, educators were there to help guide the way.

“I think I knew probably by the eighth grade that I wanted to be a teacher,” Greene said. “David Jones, I think, solidified it for me as my math teacher in high school when he just said, you really do have potential to do a lot more in mathematics and you really ought to pursue that.

“I was an insecure kid, so for somebody to sit there and say that they believed in me and that I could pull that off, it’s great.”

Maybe not in Polk County, but education will remain part of Aaron Greene’s life going forward.

He won’t be working full-time – there’s too much he wants to do outside of a job. There will be time on the golf course, maybe a long road trip with his mom. With Mary Greene also retiring, the two will be free to travel to see their son, Grayson, whenever is convenient.

But Greene feels he still has much left to give to education, and he feels that’s needed.

“I don’t think I can turn off the whole education thing,” he said. “I believe in it too much. And what I have seen recently is a real paucity of leadership in terms of people willing to step into those roles. And so we need to nurture those individuals, support them, and that’s what I’m looking forward to.

“I’m going to be working with a consulting group that does principal coaching, works with district administrators, will help districts with strategic planning. And I’ve been fortunate enough to be kind of in what they call the small district side of things. And so I’ll be trying to partner with our small districts. I’ve had that experience with our small rural schools consortium, been in charge of that for nine years. And so I’ve got a really good relationship with those districts. So I’m looking forward to doing that, to keep growing these educational leaders and hopefully helping school districts with making sure they have a continuity of leadership and an understanding of what that flywheel can do for you if you get it going.”

As he’s cleaned out his office at Stearns, memories have mixed with mementos. Letters from parents have sparked thoughts of the challenges of the past few years. Old budgets have recalled the fights for funding. Thank-you notes have brought a smile and a laugh.

Thirty years of teaching and leading creates a lot of personal accomplishments, yet all of those take a backseat to anything Polk County Schools achieved.

“It sounds so cliche, but I truly do mean it – I look back at the things we accomplished together and to bring this many people, this many different cogs of the machine together and have it function in the way that it does, is what I’m most proud of,” he said. “And that certainly means that you have to have everybody pull it in the same direction. So I’m proud of that.

“I’m proud of what Polk County Schools has built over the last three decades. I tell the story all the time about when I got here, I was told Polk County was pretty happy being mediocre, and we had just merged the county and the city school systems. And so to watch that and to be a part of that in your career, to see that upward trajectory like a roller coaster, we keep clicking, clicking, clicking, clicking. And then when you do get to go down the other side and realize, man, look what we did. That’s what I’m proud of.”

As Greene has been celebrated and given farewell fetes, many have often pointed to his leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic as one of the highlights of his career. With uncertainty gripping the community, Greene became the voice of reason and hope, punctuating each phone call to families with a reminder that “better days are ahead.”

Concern for the community mingled with unyielding optimism – it’s not a bad legacy to leave.

“Whether I want it to be or not, people probably come up to me the most about COVID and about being at least some form of stability there,” Greene said. “When you have a microphone, it’s easier to get things out. But I tell people I made calls every night and the reason I did that was more for me than it was anything else, to keep me sane, to keep me focused and keep me on track.

“So I hope that my legacy is that that guy gave everything he could for kids and for families and for his community. And so I hope that’s what people see me as, a genuine individual who really went above and beyond because he believed and cared about the kids in the community.”

There’s certainly no trophy needed to note that.